DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING

Directed by Lucio Fulci. 1972. Italy.

I. CONSERVATISM AND FEAR OF THE OTHER

For all their erotic happenings, hip modern dressings, and almost avant garde indulgences, the giallo, like most Italian popular cinema, is deeply conservative in nature. It’s a rather strange pairing. Much like the slasher films it would go on to inspire, the giallo seems at odds with itself, offering up visual orgies of decadence and debauchery only to chide the audience for their audacity in enjoying it all. Unleashed at full potential during the more relaxed censorship standards of the 60s and 70s, the giallo film regularly deployed taboo subject matter for ticket sales while simultaneously presenting the material in a framework that was cynical to the core and rife with moral condemnation. On the surface level, they were sheer carnal bacchanal crammed full of immorality, but below that gaudy yet enticing surface beat the cold heart of 1940s Italian politics.

It’s deliciously ironic that the jet set crowd was lured to Italy by the films of Fellini and Antonioni. Popular films set in gorgeous locations, dripping with machismo and ferocious femininity, practically oozing style and sexy haute couture, films like Fellini's LA DOLCE VITA were international sensations and major boons to the Italian tourist industry. But the point of those films, especially the aforementioned LA DOLCE VITA, seemed to be lost on those eager to experience the wonder of it all first hand. Fellini’s “sweet life” was nothing more than a bad joke, a painting over of the moral and intellectual decay running rampant in the streets of Rome. Fellini’s lead, a gossip journalist named Marcello, is a man swallowed up by excess, desperately trying to find meaning in all the noise and clamor of a life not worth living, only to wind up little more than a distant burn out. The “sweet life” - if it exists at all - can only be attained at the cost of your soul.

The giallo film, by and large, played the same game. They were mostly set in recognizable locations, always careful to pick post card-worthy settings for their set pieces, and constructed like travelogues to appeal to foreign audiences. They were filled with gorgeous women and handsome men, packed with lascivious moments and playful nudity, all wrapped up in a package that promised their audiences moments of wanton destruction and cruelties that would make them cower in fear. And while they were entertaining – I would even go so far as to call some gialli ground breaking – the messages beneath their attractive facades oftentimes reeked of contempt.

There is a sharp undercurrent of xenophobia in Italian popular cinema of the 60s and 70s but nowhere is this xenophobia more evident than in the giallo film. Even though the main characters of these films are usually foreigners on vacation, they are sometimes simply Northern Italians in a Southern Italian setting or vice versa, and although the murders and misdeeds that set the plot in motion occur within the diegetic past (sometimes present) of the narrative, there is a sense that these transgressions are somehow caused by the arrival of new blood in an insular society. The foreigner is looked at with suspicion, usually targeted by the police as a suspect and almost always targeted by the killer as a threat. The pervasive suggestion that modernity, a change in the customs and attitudes that had existed unchallenged in Italy for decades, and/or foreign “interference” in what was, up until the end of the 50s, a very gated country, is somehow to cause for the murders, blackmails and labyrinthine conspiracies at the heart of these turgid tales, is perhaps the most recognizable backdrop for the giallo narrative.

There is a scene in Sergio Martino’s exquisite YOUR VICE IS A LOCKED ROOM AND ONLY I HAVE THE KEY where Luigi Pistilli’s bitter writer sums up the Italian attitude towards the influx of tourists into their small, idyllic towns and villages. “They’re all poison”, he surmises and this attitude runs through Lucio Fulci’s giallo masterwork DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING. In Martino’s film, Pistilli holds nightly gatherings at his remote villa, flooding its rooms with disenfranchised hippies and vagabonds, watching as they dance and screw and smoke weed and generally live a useless life. He regards them with equal parts fascination (because they represent a life completely alien to his own) and condemnation (because the life they live is poisoning the traditional culture he holds as superior). These carefree youth are treated as curious cultural abnormalities. But much in the same way we look at insects with a curious fascination, they are nevertheless invaders in our homes. A serial abuser to his long suffering, possibly mentally ill wife, what finally brings Pistilli down is not hubris or poetic justice. It’s his niece, fashionable and full of modern sexuality, pumped full of big city ideals and moral corruptions, who finally brings about his destruction.

II. THE FILM

When asked about storytelling economy, my go-to example is always the opening three minutes of Alfred Hitchcock’s REAR WINDOW. The amount of information contained in those three minutes is impressive, all the more so for not including one single line of dialogue.

We begin with a shot of a window, the curtains rising over the main credits. This situates us within the film. This will be our viewpoint throughout almost the entire running time, our eyes gazing at (and scrutinizing) every action going in the large apartment complex just outside that window. Each apartment is designed in a way that easily facilitates our voyeurism. Large open windows reveal the inhabitants to us in plain, unobstructed views. We move then to Jimmy Stewart sleeping, his face wet with perspiration and a brief shot of a thermometer that threatens to reach 95 degrees. We see the morning routines across the way. A man shaves. A buxom blonde stretches in a barely there outfit more suitable for the beach than the big city. A couple wakes up after spending the night sleeping on a mattress placed on their balcony. All of these people will become OUR neighbors as the film plays out. We then move from Stewart’s sleeping face to his leg, wrapped in a cast. He’s sleeping in a wheelchair. A message scrawled upon his cast reads “here lie the broken bones of L.B. Jeffries”. We move to a broken camera, a shot that reveals not only the financial occupation of our main character but ties his voyeuristic tendencies to our own. The next move reveals a picture of a race car hurtling towards the camera, followed by several photographs of wreckage and destruction, telling us not only how Jeffries ended up in that wheelchair but that his personality is reckless, aloof and prone to self destruction. The final move reveals a fashion magazine, the photographic work on its cover bland and lifeless. This is the life and times of L.B. Jeffries. All of that is conveyed through mise-en-scene, set decoration and a few edits.

Fulci’s film has a similar sense of economy with its opening few minutes, only this time the economy is thematic. We begin with a postcard worthy shot of an idyllic, old time Italian village before panning over to reveal a modern highway. Like the cannibal films of the 1970s and the classic cowboys and Indians American westerns of 1950s, the old (or uncivilized) coming into contact with the new (or civilized) will be at the heart of the conflict here. We are then presented with a pair of short scenes. The first is of a village woman named Maciara digging up the skeleton of a small child. Free from proper context within the narrative, we might believe this is just an extension of the theme, a past crime somehow coming back into the diegetic present. This is paired with a scene of a child, no more than twelve, casually shooting a lizard with a slingshot. Both scenes are framed against the encroaching modernity of the highway.

We then move into the village of Accendura. Over the carefully edited shots of the village, church bells ring. We move into the church. Another young boy waits patiently while his friend gives confession, his shifting eyes peering out from between his fingers. The boys sneak out and run off to meet their friend. Together, the three boys make their way to a house near the edge of the village to sneak a peek at a pair of big city prostitutes arriving in town to service a couple of locals. The boys taunt the village idiot, Guiseppe, before running off. Throughout these opening scenes, we witness Maciara crafting a set of three wax dolls. She sticks pins through their bodies.

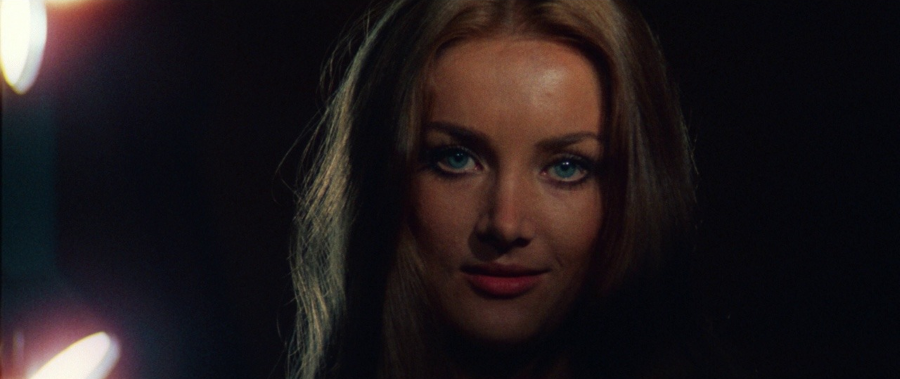

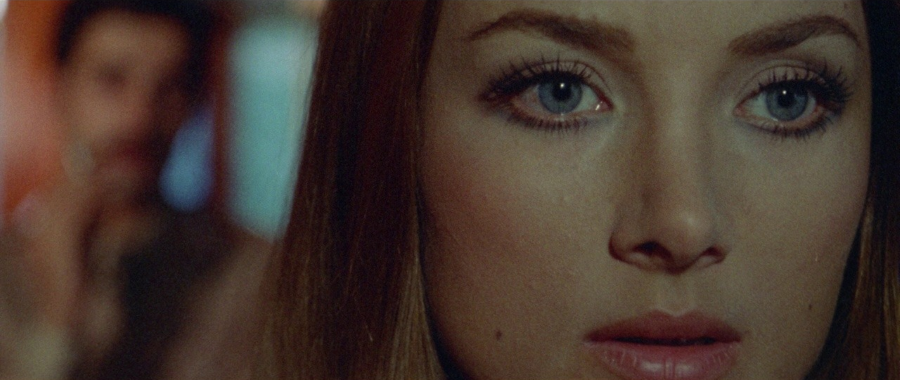

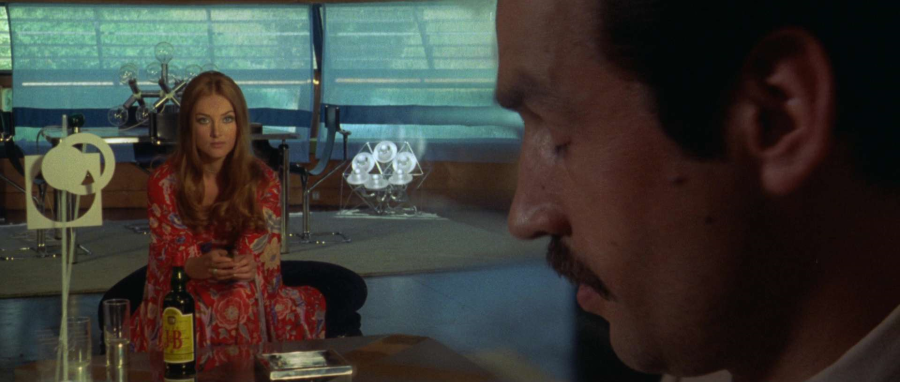

One of the boys, Michele, returns home and is told to take a beverage tray upstairs to Patrizia, a big city woman on forced holiday in the village, her ancestral home, after becoming embroiled in a drug scandal in Milan. Reclining nude beneath a sunlamp, Patrizia flirts with the young boy, even asking him if he would like to sleep with her. Later that night, one of the three boys, Bruno, goes missing. Bruno’s father receives a phone call asking for money in exchange for Bruno’s safety. Guided by the police, the father delivers the ransom money. When the kidnapper, Guiseppe, shows up to retrieve the money, he is immediately arrested by the police. After Bruno’s body is found buried in the woods, Guiseppe confesses to the plot. Only he claims to have not killed Bruno. The boy was already dead when he came across him and the ransom scheme was just a way of getting some money, presumably so he too can afford a romp with the prostitutes. His story is believed by the local police commissioner and by a reporter from the North side of Italy, our lead character, named Martelli.

A short while later, Michele receives a phone call at home. Sneaking out of the house to meet whoever it was on the other end of that telephone, Michele is strangled to death in a forest clearing, right beneath a statue of Christ. We immediately suspect the almost predatory Patrizia, shown here just outside a phone booth in the middle of nowhere. Patrizia has spent many nights driving up and down the highway for hours. When she is interrogated by the police after Michele’s body has been discovered, she claims to have driven all night, never stopping. We know that is a lie.

We meet Don Alberto, the village priest, a young, good looking man taken to playing soccer with the young boys. We also meet his mother, the quiet, reserved Aurelia, and his sister, a deaf mute child perpetually carrying a headless doll around with her. At Michele’s funeral, Maciara makes an appearance, sneaking in the entrance and beating a quick retreat when Michele’s mother has an emotional breakdown. Noticed by the police, Maciara is the subject of a manhunt. Although her mentor, a black magician (and father to the child we saw Maciara digging up at the beginning of the film) can’t offer up her whereabouts, the police eventually track her and arrest her.

Maciara claims to have murdered the children but not through strangulation. Angered by their prying around her child’s burial site and sick of their near constant harassment, she fashioned herself three voodoo dolls, bringing death upon them by sticking them with pins. When a police officer claims to have spotted Maciara miles from the scene of the last murder, Maciara is cleared of all charges and released. The next day, while wandering through an old churchyard, she is viciously beaten by four local men as retribution for her “crimes”. Mortally wounded, Maciara crawls to the edge of the village and, in plain view of passing motorists, dies.

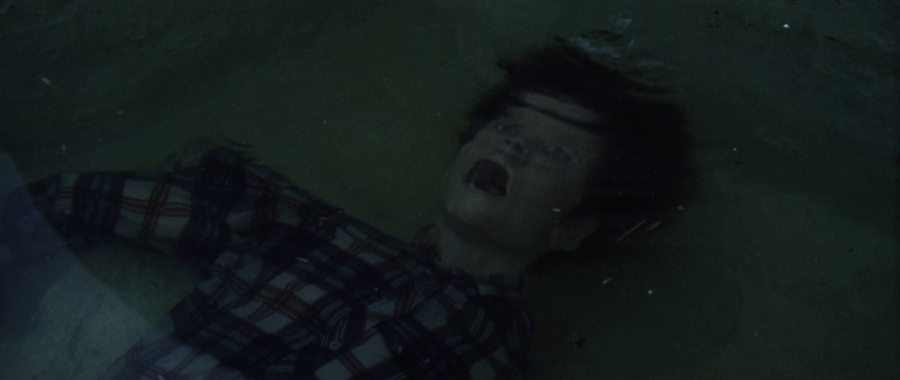

Believing the murderer to be dead, the last of the three boys, Mario, heads off to eyeball the prostitutes at the now familiar whoring house. After one of his friends squeals on him, Don Alberto heads off to bring Mario back. During his travels, Mario meets Patrizia, her car sitting still with a flat tire on the side of the road. She offers him “money or a kiss” in exchange for changing her tire. That’s the last time we see Mario alive. His body is discovered by Don Alberto, bludgeoned with a rock and drowned in a puddle of water. Martelli discovers a gold lighter near the murder site. Knowing she is the only person in town who could afford such a thing, Martelli confronts Patrizia. Again interrogated by the police, Patrizia comes clean. She is bored with the town and spends her nights driving, sometimes stopping to make a phone call to an old supplier who may or may not be able to sell her some weed.

Cleared of suspicion but told not to leave the village, Patrizia joins Martelli in trying to crack the case. Their first clue is the head of a Donald Duck doll found near Mario’s body. Patrizia had recently purchased the doll for Malvina, Don Alberto’s sister. They correctly deduce that Malvina must have seen the killer strangle one of the young boys and acted out the same behavior on her dolls, removing the heads by accident. They try to track Malvina down, fearing that her life might be in danger but are told by Don Alberto that his sister and Aurelia have gone missing. They find them hiding out on a hillside just before the young girl can be tossed to her death off the side of a jagged cliff.

Only Aurelia is not the threat. The killer is revealed to be Don Alberto. Fearing the loss of innocence the young boys will experience due to the ever encroaching modern lifestyle of loose morals and looser women, Don Alberto murdered the boys, sending them to Heaven pure. During a struggle with Martelli, Don Alberto falls to his death.

Fulci’s film, which the director co-wrote with Gianfranco Clerici (the screenwriter of CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST) and longtime collaborator Roberto Gianviti, is almost obsessively concerned with doubles. These pairings of old and new sensibilities and representations is what makes DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING such a fascinating film to watch. It has a relatively simple construction by giallo standards, relying more on the audience’s intuitions and inward morality to provide the twists, turns and surprises than just piling on red herrings and distractions. But of the most interesting doublings offered, it’s the pairings of religion in the film, the long forgotten magicks and witchcrafts of decades past versus the more modern, though not necessarily more “advanced”, Catholicism, that fascinate me the most. Together with the films views on sexuality and modern morality, these are the conversations within the film that raise DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING up to a unique level of greatness within the catalog of the giallo.

III. RELIGION, SEXUALITY AND THE FANTASY OF PURITY

I attended both a Catholic grade school and a Catholic high school. I spent twelve years of my life swimming in church doctrine, learning hymns and prayers, religious morality and fundamentalist revisionist history. I did all of this as a non-believer, non-baptized and therefore unsaved from my inherent sinfulness. Without the parental reinforcement of what I was being taught in school every day (my parents were non-believers), everything I witnessed, everything I was taught about the Bible, about Jesus and his miracles, about the saints and their martyrdom, was no more than mythology to me, no different than the tales of Hercules and Perseus that I read so much of as a child. As my friends prepared to take their steps through the sacraments, I sat silently with them, memorizing the steps and prayers that I personally wouldn’t take and wouldn’t say. During mass, I was to genuflect and stand when required. Other than that, I just had to remain silent. It was all so strangely fascinating to watch. Here were my friends, all of whom believed something I did not, all of whom felt their religion was true as strongly as I felt that it was all nonsense. I was immune to the power of the prayers. For me, they had all the power of saying “Bloody Mary” three times whilst standing in front of a mirror, which is to say, no power at all. The only thing about their beliefs that I ever shared was the fear.

I’m cured of it today. I no longer feel it, even if I can now recognize how ingeniously, devilish devised it is. The fear of hell, the fear of eternal punishment, is something drilled into children day in and day out in religious education. The anxiety it can produce, not just in childhood but throughout the life of the believer, is quite profound. It is, pardon the pun, hell to be a young child in a religious environment. Not only does lying or stealing a crayon mean that Santa Claus won’t bring me the Super Soaker I wanted, Jesus would sentence me to never ending torture too. So much fear ran through my little body as a child. There are non-believers today, grown into adulthood and long separated from their faith, still suffering from this fear. Recovering from Religion and organizations like it offer services to non-believers tormented by that last niggling bit of doubting fear: “what if I’m wrong?”

Much of this anxiety is focused on what I would consider – and what most people would consider – normal human behaviors, many of which we have no real control over. In most of my conversations with believers, I’m assured that if I don’t believe in God, I will be sent to hell for all eternity when I die. Their suggestion is to simply “believe”. This wrongly assumes that belief is a choice, that I could simply flip some subconscious switch and suddenly be filled with belief in God. Only this isn’t how belief works. Belief is not a choice. I can proclaim belief all I want but it would only be a lie. I won’t go deep into epistemology and the foundations of belief. I will only say that beliefs are formed on a subconscious level with acceptance of a truth claim based on internally held standards of evidence, preconceptions about the phenomena in question and the relation between our understandings of a subject versus our willingness to accept authority. We don’t simply “choose” to believe in anything. So if I die unable (not unwilling) to believe in God and it turns out God does in fact exist, I will have no choice but to accept punishment for a crime (not believing) that I could not help but commit. To most Christians, this is justice. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The most normal human behavior, sexual attraction/longing/desire, is perhaps the most slandered by religious teachings. From a young age, I was taught that sex is just for marriage. In fact, sex outside of marriage wasn’t referred to as “sex” at all. It was called “fornication”. The former was considered God’s intended purpose and was therefore “good” while the latter was considered a rejection of God’s chosen way and was therefore “sinful”. Of course, the idea that sex can result in procreation therefore sex is only for procreation is a naturalistic fallacy, but that didn’t matter to any of my teachers. The only thing that mattered was that I, someone with a budding natural attraction to girls when I was in grade school and a full blown attraction to girls in high school, was somehow “sullying” the idea of sex and sexuality by having these feelings outside of a marriage. Imagine a group of youngsters, all approaching their teenage years, all discovering this attraction to the opposite (or same, depending) sex, being filled with all of this natural curiosity and desire, all being told that what they’re feeling is “bad”, “sinful” and/or “dirty”. Imagine them, slightly embarrassed by their new found crushes, their bodies changing rapidly, the confusion and trepidation of sexual awakening… Now imagine those same young boys and girls sitting in a confessional being judged for the crime of simply being human. Being a young, barely teenage boy in a judgmental, slightly sinister environment like a Catholic school was troubling at times. It was bad enough I was going through puberty. Now every erection I got was inching me ever closer to an eternity of torture.

If I were a girl, it would have been even worse. In medieval times, women were little more than bargaining chips in marriage, property to be traded. It was no different in Biblical times either. As women were treated as property by territorial males, virginity was of the utmost importance. Taking a woman’s virginity was no different than staking your country’s flag into freshly discovered soil. This attitude has survived, more or less, into modern times. I’ve always found it more than a little bit disturbing that a woman’s worth is determined by the status of her hymen. Women who lose their virginity on a whim or to a mere acquaintance are looked at differently (sometimes even by other women) than someone whose first sexual encounter was with their longtime boyfriend or husband. Women are constantly shamed for their sexual escapades, something men rarely have to endure. The Madonna/whore dichotomy created by years of deeply instilled, patriarchal-led shaming of women for their simple enjoyment of sex (not to mention the ever-going war against readily available female contraception and abortion that threatens to reduce women to slaves of their biology) has bled through medieval times and has infected modern culture to a startling, though unsurprising, degree. Taken to extremes, this obsession with female purity has led to cultures where women need to be covered head to toe so as not to incite male lust, which would be a sin, even if they really were not to blame for the thoughts and actions of another individual. And the less said about female genital mutilation, almost entirely religiously motivated and done for the sole purpose of robbing women of sexual enjoyment, the better.

And what does this all have to do with DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING? Well, let’s see. We can start with the idea of religion and the cultural acceptance of it, and how Fulci uses it to create distrust and misdirection.

IV. CATHOLICISM AND WITCHCRAFT

The opening scene of the film, Maciara digging up the skeletal remains of her child, is complete free of all context. We immediately assume guilt on her part, both for the death of that child (which is never fully explained) and for the deaths we are about to witness. The setting of DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING is one of the most interesting aspects to the film. The village of Accendura is looked at as a cultural artifact, in many ways preserved in time by its segregation from the outside world. The sprawling modern highway that exists just outside its boundaries might offer a way into the village but it doesn’t seem to offer a way out. It’s telling that the village men don’t leave Accendura to have relations with prostitutes. The prostitutes come to them. With the exception of the children, no one in the village seems at all interested in even seeing the outside world. When the outside world does come to them, it’s always female in nature (either the prostitutes or Patrizia) and it always brings with it a taste of a world foreign to their own and the fear that naturally causes.

The villagers of Accendura live in a world where the supernatural forces of black magic, voodoo dolls and witchcraft coexist with traditional Catholicism. What’s interesting is how those two religions are presented here. While we immediately come to distrust Maciara for her involvement with black magic, as the film progresses the black magic she is seen practicing is revealed to be little more than rural superstition. We know Maciara isn’t to blame for the death of the children. We learn from the first murder that the boy was strangled. Yet Fulci keeps showing scenes of voodoo dolls, Maciara sticking pins through their bodies. We keep hearing about magic, even though the film explicitly tells us that magic has nothing to do with it (even if the film reverses that stance, in a way, at the end) and we still distrust this woman. We still feel like she is probably to blame for the death of the children. Why?

The ultimate irony of the film, the murder of Maciara, answers this question for us. While the police (and the viewer) know that Maciara is not guilty of the murders, she is still viewed as guilty by the villagers. That Maciara is beaten to near death in a church yard is one of the film’s most bitter, most cynical details. The men who murder her could be seen as either suffering from the side effects of a culture that granted arcane powers to voodoo dolls or suffering from the extreme religious indoctrination of Christianity that holds it as God-given law that thou shalt not “suffer a witch to live”. Either way, this brand of vigilante justice, horrific and cruel, is religiously inspired. The film doesn’t see it any other way and neither can the viewer.

Beliefs foreign from our own, especially religious beliefs which are, so we’re told, granted to us by an all-knowing, all-perfect creator of the universe, are immediately viewed as suspect. It doesn’t matter that all three of the great monotheisms are little more than plagiarisms of one another, the devil is in the details. But oddly enough, the ideological differences between Judaism, Islam and Christianity are relatively minor. They’re literally three flavors of the same bullshit. So when an Islamic suicide bomber commits an act of terror, he is branded an Islamic extremist in the United States, his act of terrorism linked to his religion. But when a Christian, pumped full of righteousness, blows up an abortion clinic, he is spared the label of “Christian extremist” in the United States. Because Christianity is OUR religion and it exists without fault (and no, I don’t believe that), even though the underlying cause of both acts was the same religion viewed through different cultural lenses.

The religious dichotomy in DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING, the arcane superstition of black magic versus the culturally accepted, seemingly benign Catholic Church, runs through the entire film, and Fulci seems to regard this dichotomy as false. What really is the difference between a superstition that regards voodoo dolls as physical conduits and a religion that believes by praying over unleavened bread you can turn it into the flesh of a God? There really isn’t one. It is all magic. The ultimate point of the film seems to be that there is no escaping the nasty side effects of believing in magic, whether that magic is culturally accepted or culturally viewed as a relic. When Maciara’s body is discovered by the police, the commissioner condemns the townspeople stating that while we can build highways “we’re a long way from modernizing the mentality of people like this”.

Given the mix of religions in the village of Accendura, it’s difficult to know which religion is to blame.

V. THY DESIRE SHALL BE TO THY HUSBAND, AND HE SHALL RULE OVER THEE

The Catholic Church’s obsession with female sexuality and the supposed inherent sinfulness within it stems from the myth of original sin. Like the Greek and Roman myths before it, Christianity holds that a woman was to blame for the fall of man, both literally and figuratively. It was Eve that tempted Adam just as it was Pandora that opened the jar. This attempt at theodicy is laced with misogyny. Eve and Pandora were the first of their kind, the first female ever created, and look at the trouble they brought with them. It’s almost as if the world would have been better off had women never been created. Heinrich Kramer, the infamous German clergyman behind the terrifyingly misogynistic call for femicide, the Malleus Maleficarum, summed up the Catholic standard view of women thusly: “women are by nature instruments of Satan – by nature carnal, a structural defect rooted in the original creation”.

The female characters in DON’T TORTURE A DUCKLING are few. We’ve already met Maciara, the wrongfully accused witch. We have Michele’s mother, a strict and shrill woman who escapes any kind of meaningful characterization. There is Don Alberto’s mother, Aurelia, quietly enabling her son’s murders. There’s Malvina, Don Alberto’s deaf mute sister. There are the two prostitutes. And then there is Patrizia, the bored, young sexpot busted for drugs. That’s not exactly the strongest bunch of characters but each serves a thematic purpose in the narrative.

Looking at Patrizia, we are presented with a problem. This is a film about a priest killing children so they can ascend to Heaven pure; that is, as virgins, spiritually uncorrupted by women. We understand that this is a ridiculous fear, that the desire for sex and the participation in it does little if nothing to harm whatever spiritual lives we may (or may not) have. We understand that sex is a human desire not to be feared and that the coloring of human sexual impulses as “sinful” is far more harmful than helpful (Fulci’s film presents us with a strange perversion of the puritanical slasher film morality; instead of “have sex and die”, we have “die so you can never have sex”). Yet when we first meet Patrizia, she is strutting completely nude in front of a child, even asking him if he would like to have sex with her. We see her later offering a child a kiss in exchange for changing her tire, an offer that ties Patrizia, even it’s just tangentially, with the visiting prostitutes who exchange carnal favors for money.

Cinema is littered with fantasy fulfillment fluff detailing the sexual conquest of an older woman by a younger man. It’s one of the most common tropes of the boy’s only B movie. In any other film, Patrizia’s introduction would have made acceptable, if a bit uneasy, erotic fodder. Barbara Bouchet was an incredibly attractive woman. It’s difficult not to gawk at her naked body as she strolls towards the camera, just as difficult as it is to not feel a bit queasy when the camera cuts back to the painfully awkward expression of a young child faced with an older, sexually intimidating woman. In his book Beyond Terror: The Films of Lucio Fulci, Stephen Thrower notes that Don Alberto and Patrizia are two sides of the same pederast coin. I’m not sure I share his opinion, at least not the pederast bit. It isn’t sexual attraction or sexual conquest that interests the two characters. It’s the power inherent in sex that serves as the parallel. Patrizia is a strong willed, sexually liberated woman, who enjoys her sexuality. Don Alberto is a repressed, fearful man, terrified of his sexuality. When Kramer wrote his Malleus Maleficarum, women like Patrizia were his targets, but Don Alberto and men like him were his target audience.

By the time the film reaches its end, this fear of female sexuality evolves into a more general fear of women. This fear runs so deep that the final scenes involve Don Alberto threatening to throw his deaf mute sister Malvina off the side of the cliff. Even a young female child is a threat to the patriarchal culture Don Alberto inhabits, if not personifies. There’s a whiff of poetic justice in the film’s final moments. During a struggle with Martelli, Don Alberto falls off the side of a cliff. His extended fall embodies the fall from grace he feared the boys would face. As Don Alberto’s body tumbles towards the earth, Fulci inserts shots of the priest’s face slamming into the side of the cliff, each impact tearing a large, bloody chunk of flesh from his skull. This image recalls the primitive (though still practiced) religious execution method of stoning, perhaps the single most called upon punishment in the entire Bible, which involves the guilty party being buried up to their waist in the ground before being pelted in the face and head with stones.

As cheap, crass and unabashedly exploitative as those final seconds are, in a film full of Biblical allusions, religious hypocrisies and disconcerting cultural attitudes, Don Alberto’s fate feels pointedly, satisfyingly perfect, something that could very well be said about the entire film.