GHOSTKEEPER

Directed by Jim Makichuk. 1981. Canada.

A trio of adults – lecherous asshole Marty, his girlfriend Jenny, and their floozy, blonde friend Chrissy - seek shelter in a seemingly abandoned hotel during a major snowstorm. It doesn’t take long for the trio to realize they’re not alone. They soon meet the hotel caretaker, an unnamed, disheveled older woman who lives in the hotel with her two sons, one of whom is far less welcoming to guests than his slightly sinister mother. The other remains unseen, locked inside a walk-in freezer deep within the bowels of the building.

That’s the general set-up for Jim Makichuk’s GHOSTKEEPER, an exceedingly quiet Canadian thriller from 1981. It’s most obvious inspiration is THE SHINING, even going so far as to borrow several major narrative cues from the Kubrick adaptation. The heroes find their only manner of transportation destroyed by the antagonist, trapping them inside the hotel. A secondary character meets a sticky end just as they arrive to help. A man freezes to death after becoming lost in the wilderness. The streak of fatalism concerning the role of caretaker is carried over. All these bits and pieces are lifted whole-hog from Kubrick’s film, but the way they’re used is very much different.

GHOSTKEEPER was a victim of its own dwindling budget, a tragic circumstance of low budget filmmaking that left the film feeling very much unfinished. GHOSTKEEPER begins with text defining the ‘Wendigo’ (or ‘Windigo’ as this film spells it), a cannibalistic, Native American monster capable of inhabiting the body of humans. This is the fate that befell the caretaker’s other son, the one locked inside the freezer in the basement of the building. The original ending would have seen the Wendigo escape it’s confines, chasing our Final Girl through the hotel in a possibly exciting climax. Starved of budget, this idea was scrapped. In fact, it feels like many third act events were either scrapped or dialed back to the point of being nigh inexplicable.

Very little of the third act makes much sense. Madness envelopes one character for no apparent reason. Another is revealed to have deep ties to the hotel, a narrative development that comes literally out of nowhere. A climactic chase scene, complete with a revving chainsaw, seems to have been tossed in for no other reason than last minute thrills. For the first two thirds of the film, GHOSTKEEPER seems to be building to something far more profound than mere insanity, but as the dollars grew thinner, the sense of narrative cohesion wasted away.

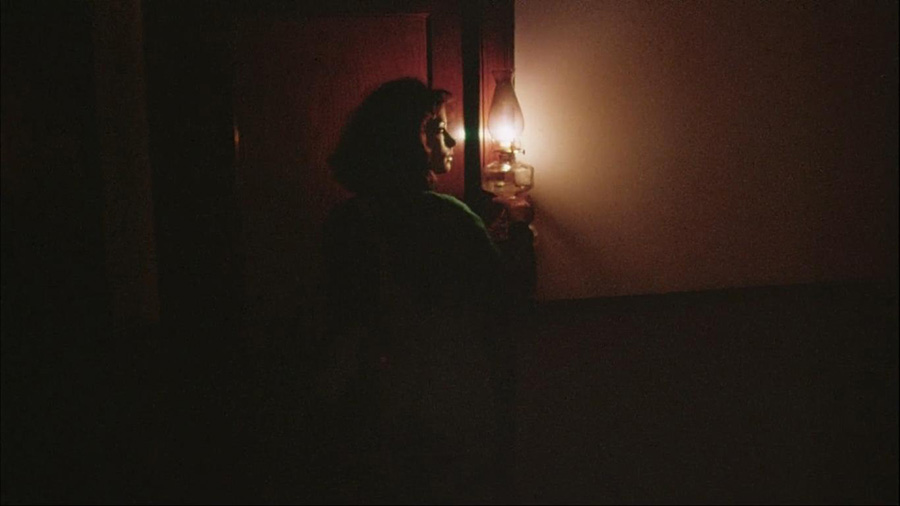

And that’s a damn shame as GHOSTKEEPER could have been something very, very special. The first 45 minutes of the film had me completely enthralled. It’s a strange film with a genuinely foreboding atmosphere. Good performances abound, the hotel setting is creepy and claustrophobic, and the Paul Zaza score (riddled with cues lifted from Zaza’s PROM NIGHT score) sent shivers down my spine. It didn’t bother me at all that the film contained very little dialogue, just endless scenes of confused and worried characters walking through an environment riddled with potential threat. It’s a good looking film too, one with a consistently cold and dangerous air about it.

The inclusion of the Wendigo, my personal favorite mythological beastie, had me excited, but my excitement soon faded once I realized that it would remain forever trapped in the freezer downstairs. The potential for drama between our three characters, one of whom has a family history of mental illness, had me wondering how and when it would all go tragically south, only to have one of those characters removed from the narrative suddenly and brutally only a half hour in. GHOSTKEEPER kept promising me a certain kind of film, only to deliver something completely different at every turn.

In some ways, that worked to its advantage. I simply couldn’t predict where the film would go next. In other ways, it dampened my excitement completely. What good is a Wendigo if you’re never going to unleash it? And that is perhaps the best way to describe GHOSTKEEPER. It’s a wonderful concept full of potentially fascinating horror moments let down by a lack of time and money. It’s a glass half empty/glass half full kind of film. Looking at what it could have been, I’m incredibly disappointed. Looking at what it actually is, I’m glad that Makichuk didn’t just shelve it and move on. It’s a beautiful puzzle, to be sure, but it’s also a little difficult to fully admire that beauty when there are so many pieces missing.