DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE

Directed by Joseph Ellison. 1979. United States.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one...

The loss of his overbearing, abusive mother sends a young man on a -

That’s what I thought. Even by 1980, the Momma’s Boy cycle of horror films was well established. Sprung from the rotten loins of Norma Bates, the PSYCHO inspired psycho movie about a troubled, usually abused, always doted over obsessively young man following the death of his mother was used, dissected, put back together and recycled more times than you could probably count on an AFRICA ADDIO sized pile of hands.

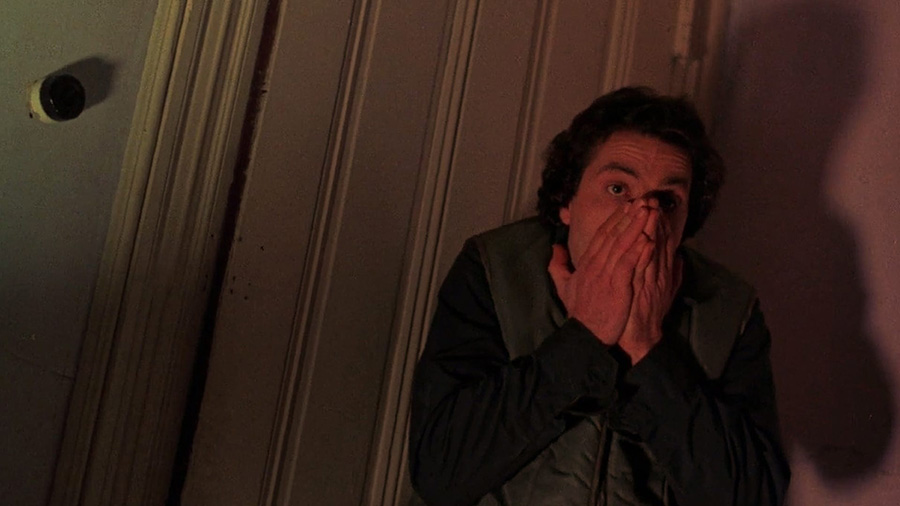

A gruesome twosome of Mommy’s Boy horror films came out in 1980. William Lustig’s MANIAC is the better known of the two, a cult classic about Joe Spinell wandering the streets of New York City, scalping women and attaching his memento moris to the plastic heads of department store mannequins. The second of those two films (though it was released first) was Joseph Ellison’s DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE. Like MANIAC, the film follows a broken, disturbed man, Donny, as he callously murders women as some form of retribution against his mother. Though MANIAC leaves much of its murderer’s history in the past, DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE begins with Donny finding his mother dead. Unable to process her passing, Donny keeps her body. In a nod to Polanski’s REPULSION with its dead rabbit, the mother’s constantly decaying corpse acts as a measuring stick of how far down the hole of madness Donny has tumbled.

At first, Donny reacts to his mother’s passing like a child would if their parents left for the evening to go to some social event. He smokes in the house, jumps up and down on a chair, and cranks his stereo up. But the memories of his abuse at her hands (she would hold his arms out above a lit burner on the stove, chiding him for being sinful) soon fuel a hateful, murderous vengeance. He constructs a crematorium of sorts in an upstairs room, lining the walls with sheet metal. He begins luring women back to his home, knocking them unconscious and chaining them to a hook dangling from the ceiling. Donny douses them with gasoline and immolates them with a flame thrower. Once they’ve expired, he dresses them in his mother’s clothing and places them in a sitting room like a collection of hunting trophies.

Both MANIAC and DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE achieve what they set out to do. They’re both grim, oppressive bits of cinema, but while MANIAC constantly tries to one-up its bloody set pieces, DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE is much more restrained. I’m not sure how MANIAC managed to avoid a place on the DPP Video Nasty list (it was banned by the BBFC but not included among the final list of 72 films) but it’s easy to see why Ellison’s film earned its slot. While the film only has one graphically violent murder (the first murder in the film at that), the image of a woman trashing about in flames is surprisingly well done and amazingly potent. You don’t need to see the execution repeated with every other victim. One was more than enough and its lingering memory turns this film into something much more violent than it actually is.

Though it’s low on the list of Video Nasties in terms of on-screen, graphic violence, it’s definitely near the top of the list when it comes to being a well made, reasonably well acted and quite effective film. There are certainly problems here. The acting is kinda wonky and everything slows to a crawl during the second act. There’s a voice over that occurs several times during the film that urges Donny on to more murders and in a twist ending those same voices are heard by a little boy being smacked around by his mom. Whether this was meant to suggest a shared experience or something a bit more supernatural, I don’t know, but I do know they come within about an inch of being campy. But despite all those flaws, watching DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE is an oftentimes entertaining, sometimes anxiety-inducing, and flat-out chilling little film that deserves a more respected place in the annals of 1980s horror.